Idiosyncratic Drug Reaction Risk Assessment

Check Your Risk

Enter information about your current medication to understand potential idiosyncratic reaction risks

Risk Assessment Results

Based on your inputs, your risk profile is:

Symptom Information

Genetic Markers

Most people expect side effects from medication. Nausea from antibiotics, drowsiness from painkillers - these are common, predictable, and usually harmless. But what if your body reacts to a drug in a way no one could have guessed? No one else had this problem. The dose was normal. The drug was approved. And yet, suddenly, you’re hospitalized with a rash that spreads like wildfire, your liver starts failing, or you develop a fever so high it feels like your body is on fire. This isn’t a mistake. It’s an idiosyncratic drug reaction.

What Exactly Is an Idiosyncratic Drug Reaction?

An idiosyncratic drug reaction (IDR) is an adverse reaction that happens in a tiny fraction of people - about 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000. It’s not caused by taking too much. It’s not because the drug is poorly made. It’s because your body, for reasons we’re still figuring out, sees the drug as a threat. These reactions are unpredictable, rare, and often severe. They don’t show up in clinical trials because the numbers are too small. Even after a drug is on the market for years, it can suddenly cause serious harm in someone who never had a problem before.Unlike typical side effects - called type A reactions - which are just an extension of how the drug works (like low blood pressure from a blood pressure pill), IDRs are type B reactions. They’re unrelated to the drug’s intended effect. A drug meant to treat arthritis might cause liver damage. A painkiller could trigger a skin condition that destroys your epidermis. And it doesn’t matter if you’ve taken the same drug before without issue. One day, your immune system flips a switch.

Why Do These Reactions Happen?

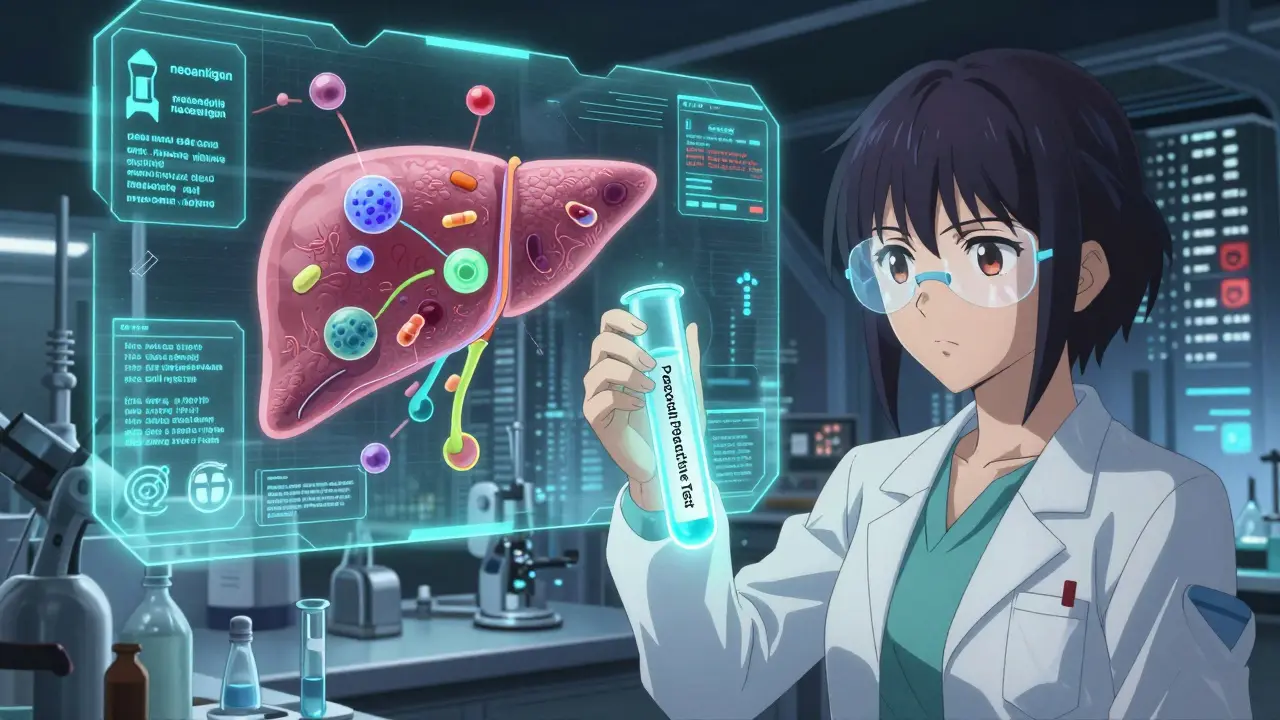

Scientists don’t have one simple answer, but the leading theory is the hapten hypothesis. It goes like this: your body breaks down the drug into reactive pieces. These pieces stick to your own proteins, like glue. Suddenly, your immune system sees a protein it’s never seen before - a “neoantigen.” It attacks. You get a rash. Your liver gets inflamed. Your lungs swell. It’s an allergic response, but not like pollen or peanuts. This is an internal betrayal.Some people have genetic flags that make this more likely. The most famous example is HLA-B*57:01, a gene variant that makes people extremely prone to a severe reaction to the HIV drug abacavir. If you carry this gene, taking abacavir can cause a life-threatening reaction. Now, before anyone starts abacavir, they get tested. If the gene is present, they don’t get the drug. It’s one of the few times we can predict an IDR - and it saved lives.

But for 92% of IDRs, there’s no such test. No genetic marker. No blood test. No warning. That’s why these reactions are so dangerous. A drug can be used safely by millions, then suddenly cause a cluster of liver failures or skin deaths - and no one knows why.

Most Common Types of Idiosyncratic Reactions

Not all IDRs look the same. The most common ones fall into two major categories:- Idiosyncratic Drug-Induced Liver Injury (IDILI): This is the #1 cause of sudden liver failure from medications. It accounts for nearly half of all severe drug-related liver damage. Symptoms include yellow skin, dark urine, fatigue, and abdominal pain. It usually shows up 1 to 8 weeks after starting the drug. The injury can be either hepatocellular (liver cells dying) or cholestatic (bile flow blocked), or sometimes both. Drugs like statins, antibiotics, and anti-seizure meds are common culprits.

- Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (SCARs): These are skin-and-body disasters. Three major types: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), and DRESS (Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms). SJS and TEN cause your skin to blister and peel off - like a severe burn. DRESS causes fever, swollen lymph nodes, rash, and organ inflammation. These reactions are deadly. TEN has a mortality rate of 25-35%. Many patients are misdiagnosed at first as having a virus or allergy.

Other rarer types include kidney damage, blood disorders, and lung inflammation. The pattern is always the same: delayed onset, severe symptoms, no clear dose relationship.

Why Are These Reactions So Hard to Diagnose?

Imagine you take a new medicine for migraines. Three weeks later, you feel tired, your skin itches, and your eyes turn yellow. You go to the doctor. They check your liver. It’s elevated. But you also had a cold last week. Maybe it’s the virus. Or maybe it’s stress. Or maybe it’s something else. The doctor doesn’t know. And neither do you.That’s the problem. IDRs mimic other illnesses. They appear weeks after the drug starts. And most doctors have never seen one. A 2021 study found that 65% of patients with IDRs were initially misdiagnosed. The average delay in diagnosis? 17 days. That’s 17 days of your body getting worse.

Doctors use tools to help. For liver injury, there’s the RUCAM scale - a scoring system based on timing, symptoms, and lab results. A score above 8 means the drug is “highly probable” as the cause. For skin reactions, the ALDEN algorithm looks at drug timing, symptoms, and whether other drugs were taken. But these tools aren’t perfect. They need experience. And most clinics don’t have that.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

The first and most important step: stop the drug. Immediately. No exceptions. Even if you think it’s helping your condition, the risk of continuing is death.Then comes supportive care. For liver injury, you might need IV fluids, liver monitoring, or even a transplant. For skin reactions, you’re often treated like a burn patient - sterile environments, pain control, wound care. Steroids are sometimes used for DRESS, but their effectiveness is debated. There’s no magic pill. Recovery can take months. Some people never fully recover. Up to 28% of those with IDILI develop chronic liver problems.

Rechallenge - taking the drug again to see if the reaction returns - is rarely done. It’s too risky. Only 5-10% of cases ever attempt it, and only in tightly controlled settings. Most doctors won’t even consider it.

Why Do So Many Drugs Get Pulled From the Market?

Between 1950 and 2023, 38 drugs were pulled from the U.S. market because of idiosyncratic reactions. Troglitazone, a diabetes drug, caused liver failure in hundreds. Bromfenac, a painkiller, killed people with liver damage. These weren’t overdoses. They weren’t manufacturing errors. They were biological accidents.IDRs are responsible for 30-40% of all drug withdrawals - even though they make up only 13-15% of all adverse reactions. Why? Because they’re catastrophic. A drug that causes mild nausea can stay on the market. A drug that kills 1 in 50,000 people? It gets pulled. The cost isn’t just lives. It’s billions. The pharmaceutical industry loses $12.4 billion a year to IDR-related failures.

Today, companies screen for reactive metabolites - the dangerous byproducts of drug breakdown - before a drug even reaches humans. Pfizer and others now set strict limits: if a drug produces more than 50 picomoles of reactive metabolites per milligram of protein, it’s scrapped. It’s expensive. It slows development. But it saves lives.

What’s Changing in the Fight Against IDRs?

There’s hope. In 2023, the FDA approved the first predictive test for pazopanib, a cancer drug that can cause liver injury. The test looks at genetic markers and liver enzyme patterns. It’s not perfect - 82% sensitive, 79% specific - but it’s a start.Researchers have found 17 new gene-drug links since 2022. HLA-A*31:01 now predicts phenytoin-induced skin reactions. HLA-B*15:02 warns of carbamazepine-related SJS/TEN in Southeast Asians. These aren’t just academic findings. They’re changing prescribing practices.

Big projects are underway. The NIH is spending $47.5 million on the Drug-Induced Injury Network. The EU’s ADRomics project is using AI and multi-omics data to predict reactions before they happen. By 2027, they hope to have a working model.

But experts warn: we’ll never eliminate IDRs. The human immune system is too complex. Too many variables. Too many unknowns. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s reduction. We’re getting better at spotting the red flags. We’re testing smarter. We’re learning who’s at risk.

What Should You Do If You’re on Medication?

You can’t predict an IDR. But you can be alert.- Know the warning signs: rash, fever, jaundice, unexplained fatigue, swollen glands, or dark urine - especially if they appear 1-8 weeks after starting a new drug.

- Don’t ignore symptoms because you think they’re “just a side effect.” If something feels wrong, say something.

- Keep a list of all your medications - including over-the-counter and supplements. Bring it to every appointment.

- If you’ve had a reaction to one drug, tell your doctor. You might be at higher risk for similar ones.

- Ask if your drug has a known genetic risk. For example: if you’re of Southeast Asian descent and prescribed carbamazepine, ask about HLA-B*15:02 testing.

Most importantly: don’t stop medication without talking to your doctor. But if you suspect a reaction, stop and get help immediately.

Final Thoughts

Idiosyncratic drug reactions are the hidden danger in modern medicine. They’re rare. They’re brutal. And they’re mostly invisible until it’s too late. But we’re learning. We’re testing. We’re connecting genes to drugs. We’re building systems to catch these reactions before they kill.For patients, the message is simple: be your own advocate. Trust your body. If something feels off, it probably is. For doctors, the message is: learn the signs. Don’t dismiss the unusual. For the industry: keep improving. Keep screening. Keep listening.

Because in the end, the goal isn’t just to make drugs that work. It’s to make drugs that won’t kill you - even if you’re the one in 100,000.

Can idiosyncratic drug reactions be predicted before taking a medication?

Only in rare cases. For a handful of drugs - like abacavir, carbamazepine, and phenytoin - genetic tests can identify people at high risk. For example, testing for HLA-B*57:01 before prescribing abacavir prevents severe reactions in nearly all carriers. But for 92% of idiosyncratic reactions, no predictive test exists. Most are still invisible until they happen.

How long after starting a drug do idiosyncratic reactions usually appear?

Most appear between 1 and 8 weeks after starting the drug. This delay is one reason they’re so hard to spot. If you develop a rash or jaundice two weeks after beginning a new antibiotic or painkiller, it’s not likely to be a coincidence. This timing is a major red flag for doctors.

Are idiosyncratic reactions more dangerous than common side effects?

Yes, significantly. While common side effects like nausea or dizziness are unpleasant but rarely life-threatening, idiosyncratic reactions can cause organ failure, severe skin damage, or death. For example, Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis has a mortality rate of 25-35%. Even liver injury from drugs can require transplants. These reactions account for 30-40% of drug withdrawals because of their severity.

Can you get an idiosyncratic reaction the first time you take a drug?

Yes. Unlike true allergies (which require prior exposure), idiosyncratic reactions can happen on the first dose. The immune system doesn’t need to be “primed.” The drug’s metabolites can trigger an immune response immediately, especially if your genetics make you susceptible. That’s why even first-time users can experience severe reactions.

What should you do if you suspect you’re having an idiosyncratic reaction?

Stop taking the drug immediately and contact your doctor or go to an emergency room. Don’t wait to see if it gets better. Document the timing: when you started the drug, when symptoms began, and what they are. Bring your medication list. Early recognition saves lives. If you’ve had a reaction before, make sure every doctor you see knows about it.

Are some people more at risk for idiosyncratic reactions?

Yes, but not in the way most people think. It’s not about age, gender, or general health. It’s about genetics. Certain HLA gene variants make you far more likely to react to specific drugs. For example, HLA-B*15:02 is common in Southeast Asians and increases SJS/TEN risk from carbamazepine. But for most drugs, no known risk factors exist - which is why these reactions remain unpredictable.

Do drug labels warn about idiosyncratic reactions?

Not well. A 2021 FDA analysis found only 42% of drug labels contain specific information about idiosyncratic risks. Most just say “hypersensitivity” or “rare side effects.” That’s why patients and doctors often miss the signs. Reliable sources like LiverTox and RegiSCAR offer more detailed clinical data, but they’re not always accessible in routine care.

How do doctors confirm an idiosyncratic reaction?

They use diagnostic tools like RUCAM for liver injury or ALDEN for skin reactions. These tools score symptoms, timing, lab results, and whether other causes are ruled out. A high score means the drug is likely responsible. But confirmation often comes from dechallenge - symptoms improve after stopping the drug - and sometimes rechallenge, though that’s rare and risky. There’s no single blood test that confirms it.

Is there any way to prevent idiosyncratic reactions?

Prevention is limited but improving. For drugs with known genetic risks, testing before prescribing is the gold standard. Drug companies now screen for reactive metabolites in early development. Regulatory agencies require more safety data. But since most IDRs have no warning signs, the best prevention is awareness - knowing the symptoms and acting fast if they appear.

What’s the future of managing idiosyncratic drug reactions?

The future lies in combining genetics, immune profiling, and AI. Projects like the FDA’s IDR Biomarker Qualification Program and the EU’s ADRomics aim to predict reactions before they happen. By 2030, experts believe we can reduce severe IDRs by 60-70% using better screening. But we’ll never eliminate them entirely - the human immune system is too complex. The goal is to make them rare enough that they’re no longer a leading cause of drug withdrawals.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

8 Comments

This is the most terrifying thing about modern medicine - we hand out chemicals like candy and assume our bodies won’t turn on us. One day you’re fine, the next you’re in the ICU because your immune system decided your liver was a foreign invader. And the worst part? No one saw it coming. No test. No warning. Just a slow-motion collapse that looks like a virus until it’s too late. We need better screening. We need mandatory genetic flags for high-risk drugs. And we need doctors to stop dismissing symptoms as ‘just side effects.’ This isn’t paranoia. It’s survival.

In India, we see this every monsoon season - patients arrive with rashes and jaundice after taking over-the-counter painkillers bought from street vendors. No one tells them about HLA-B*15:02. No one tests. The system is broken. We have millions taking carbamazepine without screening. And yet, we still call it ‘modern healthcare.’ This isn’t just a Western problem. It’s a global failure of precaution. If we can map the human genome, why can’t we map who’s at risk before giving them a pill?

I had a friend who got DRESS from an antibiotic. Took three months to recover. She still gets fatigued if she takes anything new. The scariest part? Her doctor didn’t even connect it until she mentioned the drug from six weeks ago. I wish more people knew - if you feel off after starting something new, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s stress. Don’t Google it. Just stop and call your doctor. It’s not dramatic. It’s smart.

Thank you for writing this. I work in a rural clinic in Uttar Pradesh, and we get patients every month with unexplained liver enzyme spikes. No one thinks to ask about meds from three weeks ago. We need training. We need simple checklists. And we need to stop blaming the patient for ‘not remembering what they took.’ Many don’t even know the brand name - they just took the little white pill the pharmacist handed them. Education isn’t luxury - it’s life-saving.

The systemic failure here is not technological but epistemological. We operate under the assumption that pharmacological safety is linear when it is profoundly nonlinear. The immune system does not obey dose-response curves. It operates in emergent states. We are applying Newtonian logic to quantum biology. Until we acknowledge this paradigmatic mismatch, our predictive models will remain as useful as a map of Mars in a hurricane.

I never thought about this before but now I’m kinda scared to take anything new. Like… what if I’m the one in 100k? I guess I’ll just keep my meds list handy and not ignore weird symptoms. Thanks for the heads up. Stay safe out there.

While the piece is superficially informative, it fundamentally misunderstands the ontological underpinnings of idiosyncratic reactivity. The hapten hypothesis is a reductive biochemical narrative that ignores the psycho-neuro-immunological feedback loops governing host-drug interactions. We are not merely pharmacokinetic vessels - we are complex adaptive systems embedded in epigenetic, microbiome-influenced, and socio-environmental matrices. The FDA’s 50-picomole threshold is a technocratic illusion - a quantification fetish that obscures the qualitative unpredictability of biological emergence. Until we abandon reductionist pharmacovigilance and embrace holistic biocomplexity modeling, we are merely rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

It’s worth noting that the FDA’s 2023 approval of the pazopanib predictive test represents the first meaningful shift in IDR management since HLA-B*57:01 screening for abacavir. The validation of biomarker-driven risk stratification in oncology sets a precedent that could be extended to other drug classes - particularly anticonvulsants, antibiotics, and NSAIDs - where the risk-benefit ratio is already narrow. This is not a cure. But it is the first step toward a new standard of care.