When a senior experiences chronic pain, the question isn’t just how to treat it-it’s how to treat it safely. Opioids can help, but they’re not a one-size-fits-all solution, especially for people over 65. Their bodies process drugs differently. They often take multiple medications. And the risks-drowsiness, falls, confusion, even breathing problems-can be life-threatening if not managed carefully.

Why Seniors Are More at Risk

As we age, our liver and kidneys don’t work as efficiently. That means opioids stick around longer in the body. Fat distribution changes too, so drugs can build up in tissues. Even a normal adult dose might be too much for an 80-year-old. And it’s not just about the opioid itself. Most seniors are on other meds-blood thinners, antidepressants, sleep aids, heart drugs. Mixing opioids with these can lead to dangerous interactions. One study found that nearly 40% of older adults on opioids were also taking benzodiazepines or other sedatives, which triples the risk of overdose.What Opioids Are Safe (and Which to Avoid)

Not all opioids are created equal for seniors. Some are simply too risky. Meperidine (Demerol) is off-limits-it breaks down into a toxin that can cause seizures and confusion. Codeine is also a no-go. It turns into morphine in the body, but older adults often can’t metabolize it properly, leading to unpredictable and dangerous effects. Tramadol and tapentadol need caution too. They affect serotonin, and when mixed with SSRIs or SNRIs (common for depression or nerve pain), they can trigger serotonin syndrome-a rare but serious condition with high fever, rapid heartbeat, and muscle stiffness. Safer options include oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, hydromorphone, and buprenorphine. But even these must be used with care. Buprenorphine stands out. It’s a partial opioid agonist, meaning it reduces pain without causing the same level of respiratory depression. Studies show it causes less constipation and doesn’t cause dizziness or confusion when used at low doses-even when paired with small amounts of other opioids for breakthrough pain.Starting Low and Going Slow

The golden rule for seniors: start at 30-50% of the usual adult dose. For someone who’s never taken an opioid before, that might mean 2.5 mg of oxycodone or 7.5 mg of morphine-half a pill, sometimes even less. Never start with a patch or long-acting version. These deliver steady doses over time, and if the initial dose is too high, there’s no way to stop it quickly. Wait at least 48 hours before increasing the dose. That’s because short-acting opioids like oxycodone take nearly two days to fully clear from an older person’s system. Rushing increases the chance of overdose. Use liquid forms if you need even smaller doses-pharmacies can compound them.Monitoring: It’s Not Optional

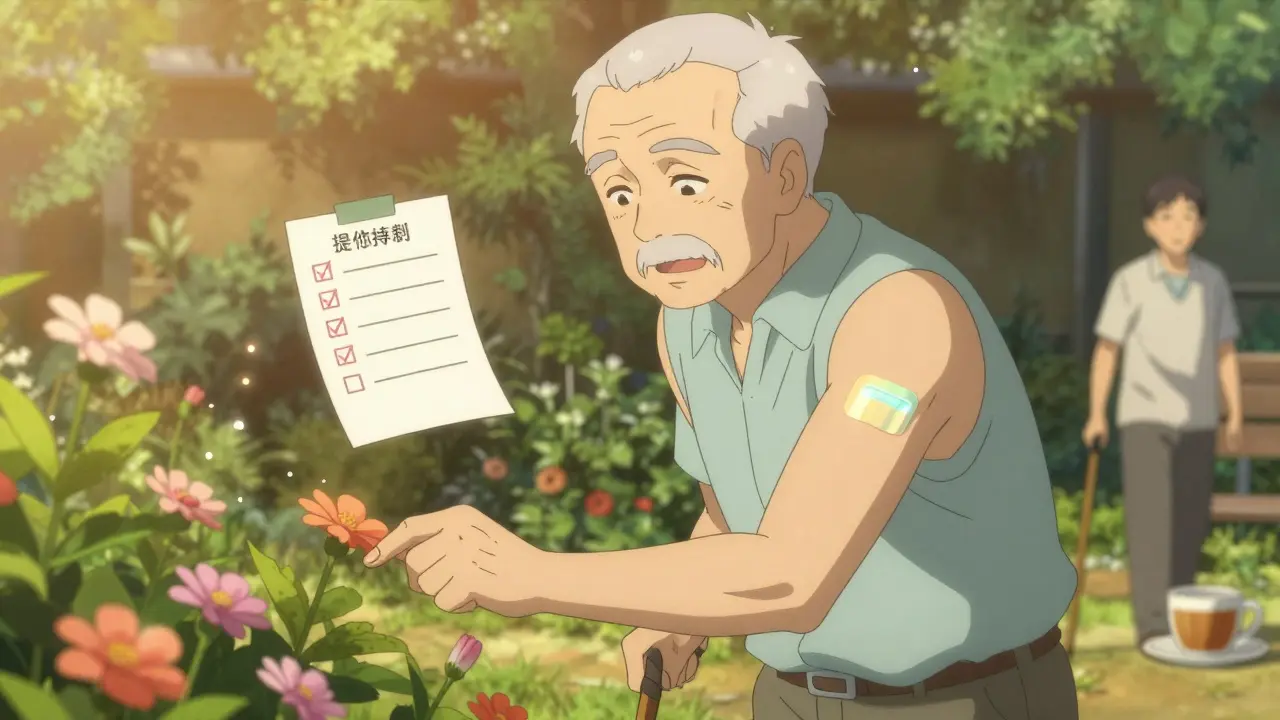

Starting an opioid isn’t the end of the conversation-it’s the beginning. Regular check-ins are mandatory. Every 2-4 weeks, assess:- Is pain improving? Not just rated on a scale, but can they get out of bed? Walk to the bathroom? Sleep through the night?

- Are there side effects? Constipation is almost universal-start a stool softener on day one. Drowsiness? Confusion? Falls? These are red flags.

- Is the patient still using the drug as prescribed? Urine drug screens help catch misuse or unexpected substances.

Don’t wait for a crisis. If a senior starts stumbling more often, seems foggy, or stops eating, stop and reassess. Delirium can sneak up fast. One study found that nearly 20% of elderly patients on opioids developed new confusion within three weeks.

Non-Opioid Alternatives-And Their Limits

Before opioids, try acetaminophen (up to 3 grams a day, or just 2 grams if the person is frail, over 80, or drinks alcohol). It’s usually safe if liver function is normal. NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen? Use them only for short bursts-no more than one or two weeks. They raise the risk of stomach bleeding, kidney damage, and heart failure in older adults. Gabapentin and pregabalin are often prescribed for nerve pain, but they’re not great substitutes. A 2023 study showed they reduce pain by less than one point on a 10-point scale compared to placebo. Worse, they cause dizziness and confusion in up to 30% of seniors. They’re not safer-they’re just different. Physical therapy, heat/cold packs, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acupuncture can help too. They don’t work fast, but they work without drugs-and they’re worth trying before opioids.The 2022 CDC Shift: Why It Matters

Back in 2016, the CDC pushed for lower opioid doses across the board. That led many doctors to cut or stop opioids for seniors-even those with cancer. But the 2022 update corrected that. It now says clearly: opioids are still first-line for moderate-to-severe cancer pain. The old guidelines were misapplied. People suffered needlessly. The new guidance says: treat the person, not the number. Don’t lock yourself into a 50 MME daily cap. If a senior with advanced cancer needs 70 MME to walk, eat, and sleep without pain-that’s appropriate. The goal isn’t to minimize dose. It’s to maximize function and comfort.What Good Monitoring Looks Like

A solid plan includes:- A written treatment agreement for any opioid use longer than three months

- Regular pain and function assessments (not just pain scores)

- Checking for signs of misuse: hoarding pills, asking for early refills, visiting multiple doctors

- Keeping family or caregivers informed-they’re often the first to notice changes in behavior

One clinic in Wisconsin started using a simple checklist: “Can they get to the toilet? Do they remember their pills? Are they eating? Are they alert?” Within six months, hospitalizations from opioid-related confusion dropped by 60%.

When to Stop

Sometimes, opioids aren’t working anymore. Maybe the pain is getting worse, or side effects are outweighing benefits. Or maybe the person’s health is declining, and the focus shifts to comfort-not cure. Don’t quit cold turkey. Taper slowly. Even if the pain is gone, the body has adapted. Stopping suddenly can cause nausea, sweating, anxiety, and muscle aches. Reduce by 10-20% every 3-7 days, depending on tolerance. And if the goal is end-of-life care? Opioids are essential. There’s no shame in using them. The goal isn’t to avoid opioids-it’s to avoid suffering.Final Thoughts: Balance, Not Fear

Opioids aren’t evil. They’re tools. Used right, they give seniors back their dignity-walking to the garden, sitting with family, sleeping without pain. Used wrong, they’re dangerous. The key is personalization. No two seniors are the same. One might tolerate 40 MME a day with no issues. Another might get dizzy on 10. The answer isn’t a rulebook. It’s attention. Observation. Communication. And never assuming that less is always better.When a senior says their pain is unbearable, don’t assume they’re addicted. Don’t assume they’re exaggerating. Assume they’re in pain-and help them, carefully, respectfully, and with full awareness of the risks.

Are opioids safe for seniors with cancer?

Yes, opioids remain the first-line treatment for moderate to severe cancer pain in seniors. The 2022 CDC guidelines specifically corrected earlier misapplications that led to under-treatment. Studies show about 75% of cancer patients respond well to opioids, with an average 50% reduction in pain intensity. The goal is comfort and function-not avoiding opioids.

What’s the safest opioid for elderly patients?

Buprenorphine is often the safest choice for seniors, especially when used as a low-dose patch. It has a lower risk of respiratory depression, causes less constipation than other opioids, and doesn’t trigger confusion when combined with small doses of other pain relievers. For breakthrough pain, doctors may add a short-acting opioid like oxycodone at very low doses.

How do I know if my parent is taking too much?

Watch for signs like excessive drowsiness, slurred speech, confusion, unsteady walking, or falling. If they’re sleeping more than usual, not eating, or seem unusually quiet or withdrawn, it could be opioid toxicity. Also check for constipation, nausea, or changes in breathing. If you notice any of these, contact their doctor immediately-don’t wait for a scheduled visit.

Can seniors take acetaminophen with opioids?

Yes, but with limits. The total daily dose of acetaminophen should not exceed 3 grams (3,000 mg) for most seniors. For those over 80, frail, or who drink alcohol regularly, stay under 2 grams (2,000 mg) per day. Many opioid combinations include acetaminophen (like oxycodone/acetaminophen), so always check the label and track total intake to avoid liver damage.

Why shouldn’t I start with a pain patch?

Patches release medication slowly over days. For someone who’s never taken opioids before, the dose is hard to adjust. If the patch delivers too much, the effects can build up over 24-72 hours and lead to overdose before anyone realizes. Always start with short-acting pills so you can control the dose and stop quickly if needed.

How often should seniors on opioids be checked by a doctor?

At least every 2-4 weeks during the first few months. After that, monthly or every other month is typical if things are stable. But if side effects appear or pain worsens, more frequent visits are needed. Regular check-ins should include assessing pain levels, function, side effects, and signs of misuse.

What should I do if my senior parent refuses to take their pain meds?

Don’t assume they’re being difficult. They might be afraid of addiction, confused about side effects, or experiencing nausea or dizziness from the medication. Talk to their doctor. Ask if the dose can be lowered, if a different opioid is better tolerated, or if non-drug options like physical therapy or nerve blocks can help. Sometimes, switching from pills to a liquid form or patch (after tolerance is built) makes a big difference.

Next Steps for Families and Caregivers

- Keep a written log of pain levels, medication times, side effects, and functional changes (e.g., “walked to kitchen today,” “slept 6 hours”).

- Store opioids in a locked box. Never leave them out.

- Ask the pharmacist to review all medications-many seniors take 8-10 drugs. Interactions are easy to miss.

- Know the signs of overdose: slow breathing, blue lips, unresponsiveness. Keep naloxone on hand if opioids are used regularly.

- Encourage open conversations. Let your senior know it’s okay to say, “This isn’t helping,” or “I feel too drowsy.”

Pain doesn’t have to be a normal part of aging. But treating it safely requires more than a prescription. It requires attention, patience, and a willingness to adjust. The goal isn’t to eliminate all pain-it’s to let a senior live well despite it.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

13 Comments

i just had to put my mom on tramadol last month and holy cow, she was so confused by day 3. like, she forgot my name and tried to call the dog 'sweetie' like it was her grandkid. we switched to buprenorphine patch and she’s back to knitting and yelling at the TV. i wish someone had told me this sooner.

my dad’s on oxycodone 5mg twice a day. he walks to the mailbox now. that’s victory.

so let me get this straight - we’re telling grandpa he can’t have codeine because his liver’s tired, but it’s totally fine to give him a 20mg oxycodone pill that’s basically a tiny nuclear bomb in a gel cap? we’re not fixing the system, we’re just swapping one bad idea for another with better packaging.

the part about starting at 30-50% of adult dose? that’s the golden rule. i’ve seen too many elderly patients crash because a well-meaning doc said 'just start with the regular dose, they’ll adjust.' no. their bodies aren’t adjusting - they’re drowning. i always tell families: if the pill looks too big, ask for a liquid. pharmacies can make it tiny. seriously, ask. it’s not weird. it’s smart.

the 2022 CDC update was a necessary correction, but the entire opioid discourse in the US remains catastrophically infantilized. we treat seniors like fragile porcelain dolls instead of complex physiological systems. the real issue isn’t the drug - it’s the medical system’s refusal to individualize care. this article is better than most, but it still operates within the confines of a broken paradigm.

you know what’s wild? we’ll let a 70-year-old with stage 4 cancer take 120mg of morphine a day to sit with his grandkids, but we’ll deny a 68-year-old with degenerative disc disease 20mg of oxycodone because 'it’s not life-threatening.' pain is subjective, yes - but so is dignity. if your mom can finally sleep through the night, that’s not addiction. that’s healing.

the real tragedy isn’t opioid misuse - it’s that we’ve turned pain management into a moral test. if you’re suffering, you’re weak. if you’re relieved, you’re addicted. if you’re alive, you’re lucky. we’ve lost the art of compassionate care. opioids aren’t the enemy. our fear is. and that fear kills more than any pill ever could.

Dear Madam/Sir, I have read your article with profound intellectual engagement and wish to respectfully offer a counterpoint based on my 17-year tenure as a geriatric pharmacist in Chandigarh. The assertion that buprenorphine is 'safest' lacks consideration of CYP2D6 polymorphisms prevalent in South Asian populations, which may lead to suboptimal analgesia. Furthermore, the omission of tramadol’s potential utility in low-dose regimens under strict monitoring is a significant oversight. May I humbly suggest a follow-up publication incorporating global pharmacogenomic data?

the CDC update was just damage control after years of ideological overreach. you can’t fix a policy failure by doubling down on the same flawed assumptions. 'maximize function' sounds nice, but function for whom? the patient or the insurance company? this article is just another polished PR piece hiding behind medical jargon. real care means letting people die in peace - not medicating them into a false sense of vitality.

i’m so glad we’re finally talking about this. but why do we still let doctors write prescriptions like they’re ordering coffee? 'oh, just take one every 6 hours' - nope. you need a full consent form, a notary, a blood test, and a signed affidavit from your cat. i’ve seen so many seniors get addicted because no one sat down and said 'this is what’s happening to your body.' we need more compassion, less paperwork. and also, please stop using the word 'senior.' it sounds like a discount coupon.

the most important thing here isn’t the opioid choice - it’s the monitoring. i’ve been a caregiver for my uncle for 5 years. he’s on morphine, and we do a daily checklist: can he get to the toilet? did he eat breakfast? does he recognize the dog? if the answer to any of those is no, we call the doctor. no waiting. no 'maybe tomorrow.' that’s how you prevent delirium. it’s not rocket science. it’s just showing up. and honestly? the fact that this article even mentions that checklist? that’s the real win here. most docs don’t even know what it means to monitor. they just refill.

in india, many elderly are given tramadol without any assessment. it is cheap, it is easy. but they become sleepy, fall, and break hips. we need education. not just for doctors - for families too. pain is not normal. but death from pain is worse.

you guys are right about the checklist. my sister started doing it for my mom - just sticky notes on the fridge: 'walked? ate? alert?' - and now the whole family checks it every night. we even made a little chart. it’s dumb, but it works. my mom says she feels like she’s part of the team now. not just a patient.