Knowing your genetic risk for cancer isn’t just about fear-it’s about control. If you’ve got a strong family history of breast, ovarian, colorectal, or other cancers, genetic testing can shift you from guessing to acting. It’s not science fiction. It’s medicine that’s already saving lives today.

What BRCA and Lynch Really Mean

When people talk about inherited cancer risk, two names come up again and again: BRCA and Lynch syndrome. These aren’t just buzzwords. They’re specific gene mutations that dramatically raise your chances of developing certain cancers.BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes. When they work normally, they help fix damaged DNA. But if you inherit a harmful mutation in one of them, your body can’t repair DNA errors as well. That means cells can turn cancerous more easily. Women with a BRCA1 mutation have up to a 72% chance of getting breast cancer by age 80. For BRCA2, it’s about 69%. Ovarian cancer risk jumps to 44% for BRCA1 and 17% for BRCA2. Compare that to the general population: about 13% for breast cancer and less than 2% for ovarian. That’s not a small difference. It’s life-altering.

Lynch syndrome is different. It’s caused by mutations in genes like MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, or EPCAM. These genes help fix mistakes when DNA copies itself. When they’re broken, errors pile up fast-especially in the colon and uterus. People with Lynch have up to an 80% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer. That’s way higher than the 4% average. Endometrial cancer risk can hit 60%. And it’s not just those two. Lynch also increases risk for stomach, ovarian, pancreatic, and even brain cancers.

Testing Has Changed-A Lot

Ten years ago, if you were worried about BRCA, you got tested for BRCA only. That’s it. Today, that’s outdated. Most doctors now use multigene panel testing. Instead of checking one or two genes, they look at 30 to 80 genes at once. This includes BRCA1/2, Lynch genes, and others like PALB2, ATM, CHEK2, and RAD51C-all linked to increased cancer risk.Why does this matter? Because people often don’t know which gene is running in their family. A woman with early-onset breast cancer might assume it’s BRCA. But it could be PALB2. A man with colon cancer at 45 might think it’s just age. But it could be Lynch. Panel testing finds more answers. A 2023 study of nearly 40,000 people found that single-gene tests missed up to half of the harmful mutations that panels caught.

Testing is also faster and cheaper. Most labs now use next-generation sequencing, which reads your DNA in minutes instead of weeks. Blood or saliva samples are all you need. Turnaround time? Usually two to three weeks. And the accuracy? Better than 99% for spotting single-letter changes in DNA.

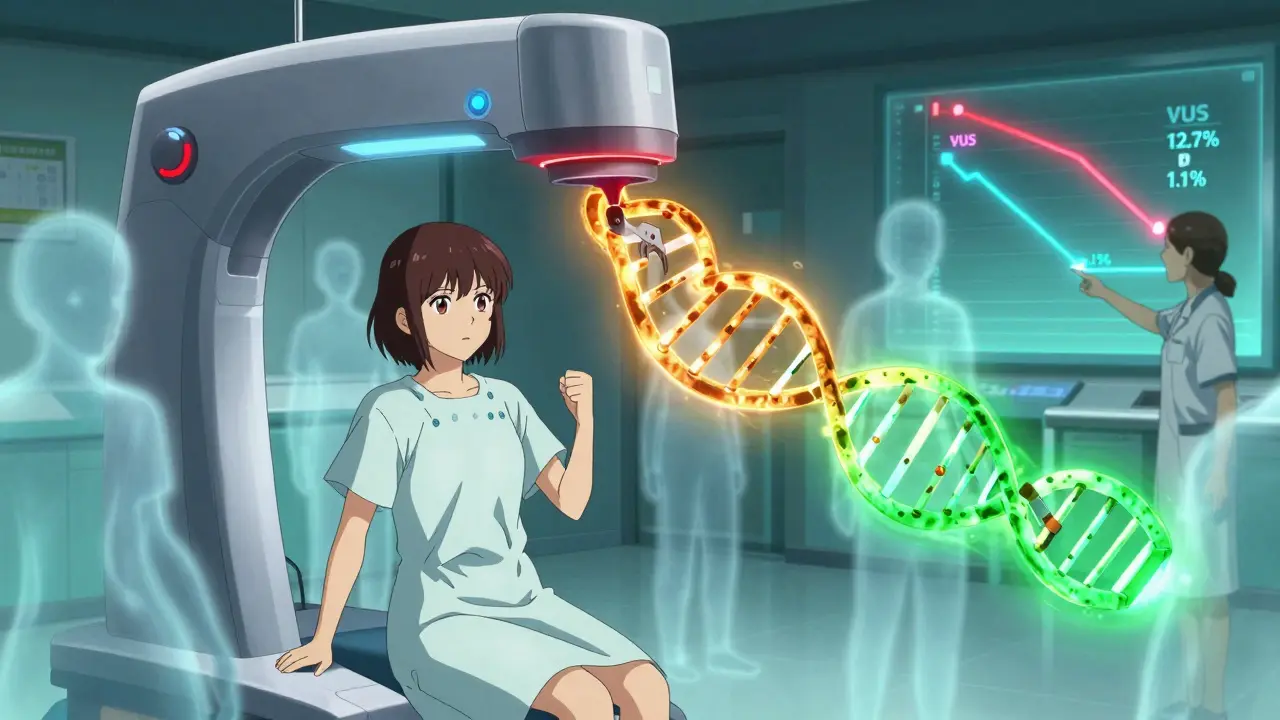

The Big Problem: Variants of Uncertain Significance

Here’s the catch. Not every change in your DNA is clearly good or bad. Some are just… unknown. These are called variants of uncertain significance, or VUS. A few years ago, about 1 in 8 people got a VUS result from a multigene panel. That meant a lot of anxiety with no clear answers.But things are improving fast. In February 2025, researchers at the Mayo Clinic published a breakthrough. Using CRISPR-Cas9, they tested nearly 7,000 different BRCA2 variants in the lab. They figured out which ones caused cancer and which didn’t. The result? In the most critical part of the BRCA2 gene, VUS rates dropped from 12.7% to just 1.1%. That’s a game-changer.

Now, labs are using this data to reclassify old results. If you got tested in 2020 and got a VUS, there’s a good chance it’s been reclassified by now-probably to either “benign” or “pathogenic.” You might not even know it. That’s why it’s important to check back with your genetic counselor every couple of years.

Who Should Get Tested?

You don’t need to be a cancer patient to qualify. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has clear guidelines. You should consider testing if:- You were diagnosed with breast cancer before age 45

- You have ovarian, pancreatic, or metastatic prostate cancer at any age

- You have multiple relatives with breast, ovarian, or colorectal cancer

- A close family member tested positive for a known cancer gene mutation

- You’re of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and have any family history of breast or ovarian cancer

Even if you don’t have cancer, but your family does, testing can help you take action. And it’s not just for women. Men with BRCA mutations have higher risks of breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancer. Lynch syndrome affects men and women equally.

What Happens After a Positive Result?

A positive test doesn’t mean you’ll get cancer. It means you’re at higher risk-and now you can do something about it.For BRCA carriers, options include:

- Starting mammograms and breast MRIs at age 25-30

- Considering risk-reducing mastectomy (which can lower breast cancer risk by up to 95%)

- Removing ovaries and fallopian tubes by age 35-40 (cuts ovarian cancer risk by 80% and breast cancer risk by 50%)

- Taking drugs like tamoxifen or raloxifene to reduce risk

For Lynch syndrome:

- Colonoscopies every 1-2 years starting at age 20-25

- Endometrial biopsies for women starting at age 30-35

- Aspirin daily (shown to cut colorectal cancer risk by 50% in Lynch patients)

- Considering removal of the uterus and ovaries after childbearing

And here’s the best part: if you have a mutation, your cancer treatment can be smarter. For example, people with BRCA mutations often respond better to PARP inhibitors like olaparib. Those with Lynch syndrome may benefit from immunotherapy drugs like pembrolizumab. Genetic info isn’t just for prevention-it’s for treatment too.

What About Direct-to-Consumer Tests?

You’ve probably seen ads for 23andMe or MyHeritage saying they test for “BRCA.” That’s misleading. These tests only check for three specific mutations common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. That’s it. They miss over 97% of BRCA mutations in other populations. If you’re not Ashkenazi Jewish and you get a “negative” result from a DTC test, you’re not safe-you’re just uninformed.These tests also don’t include Lynch genes, PALB2, or any of the other 60+ cancer risk genes. They’re not designed for medical decisions. They’re designed for curiosity. Don’t rely on them for health planning.

Insurance, Privacy, and Costs

Many people worry about insurance discrimination. That’s why GINA (the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act) exists. It stops health insurers and employers from using your genetic data against you. It doesn’t cover life, disability, or long-term care insurance, though. So if you’re thinking about buying those, be aware.Costs vary. In the U.S., Medicare and most private insurers cover testing if you meet NCCN criteria. Out-of-pocket costs for those without coverage can range from $250 to $500 for panels. Some labs offer payment plans. Re-testing for VUS reclassification? That can cost extra-around $250-so ask upfront.

Privacy? Labs follow HIPAA and NIST security standards. But there have been breaches. In 2024, over 400,000 people had their genetic data exposed in three separate incidents. Choose a reputable lab with a strong track record. Ask how they store and protect your data.

The Reality: Not Everyone Gets Tested

Despite how powerful this tool is, most people who qualify don’t get tested. Only about 33% of eligible cancer patients in the U.S. get genetic testing. The gap is wider in community clinics and among Black and Hispanic patients. Reasons? Lack of awareness, long wait times for counselors, cost barriers, and fear.But things are changing. More cancer centers are embedding genetic counselors into oncology teams. Electronic health records now auto-flag patients who meet testing criteria. In 2025, 87% of U.S. cancer centers have integrated testing into their standard workflow. That’s progress.

What’s Next?

The future is coming fast. Researchers have identified over 380 DNA changes that affect how genes turn on and off in cancer. These aren’t single-gene mutations-they’re subtle switches that nudge your risk up or down. Soon, we’ll combine all of this into polygenic risk scores. Imagine knowing your overall genetic risk for breast cancer-not just from BRCA, but from hundreds of small signals added together.Some experts believe we’ll eventually test everyone with cancer for germline mutations-not just those with a family history. Why? Because it changes treatment for everyone. And it helps their family members too.

But we’re not there yet. For now, the best thing you can do is talk to your doctor if you have a family history of cancer. Ask: “Should I be tested?” Don’t wait for someone to bring it up. Be your own advocate.

Genetic testing isn’t about predicting doom. It’s about gaining power. The power to screen earlier. To prevent. To choose. To live longer. And to protect the people you love.

Does a negative genetic test mean I won’t get cancer?

No. A negative test only means you don’t have the specific inherited mutations tested for. You can still get cancer from lifestyle, environment, or random DNA errors. Most cancers aren’t inherited. Even if your test is negative, follow standard screening guidelines-mammograms, colonoscopies, skin checks-based on your age and personal risk.

Can I get tested if I don’t have cancer?

Yes. In fact, testing is often more useful before cancer develops. If you have a strong family history, testing can help you start early screening or preventive steps. For example, a woman with a BRCA mutation might choose to have her ovaries removed before cancer starts. That’s prevention, not treatment.

What if I get a VUS result?

Don’t panic. A VUS means the lab found a change in your DNA, but they don’t know yet if it causes cancer. It’s not positive or negative. Most VUS are later reclassified as benign. Ask your genetic counselor to check back in 1-2 years. Many labs automatically notify you if your result changes. Don’t make medical decisions based on a VUS alone.

Is genetic testing covered by insurance?

In the U.S., Medicare and most private insurers cover testing if you meet NCCN guidelines-like having early-onset cancer or a strong family history. Out-of-pocket costs can be $0 if you qualify. If you don’t meet criteria, expect to pay $250-$500. Always check with your insurer and the testing lab before proceeding.

Can my employer or health insurer use my results against me?

No, under U.S. law (GINA), health insurers and employers cannot use your genetic test results to deny coverage or employment. But GINA doesn’t cover life insurance, disability insurance, or long-term care insurance. Those companies can ask for your results and use them to deny coverage or raise rates. Be cautious if you’re applying for those.

Should I test my children?

Generally, no-unless there’s a medical reason to act during childhood. For genes like BRCA or Lynch, cancer risk doesn’t appear until adulthood. Most experts recommend waiting until age 18-25 so the person can make their own informed choice. Testing kids can cause unnecessary anxiety and doesn’t change medical care until they’re older.

What if my test is positive but no one else in my family has cancer?

That’s more common than you think. Sometimes mutations skip generations, or family members died young from other causes before cancer could develop. A positive result still matters. It means you’re at high risk-and your blood relatives may be too. Encourage them to get tested. You might be the first person in your family to know.

Do I need a genetic counselor to get tested?

You don’t legally need one, but you absolutely should. Genetic counselors help you understand what the test can and can’t tell you, what your results mean for you and your family, and what your next steps should be. Most labs require counseling before and after testing. If your doctor doesn’t offer it, ask for a referral.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

9 Comments

I never knew BRCA could be this detailed. My aunt had breast cancer at 38, and we just assumed it was bad luck. Now I’m wondering if I should get tested. Not scared, just curious.

Found out my mom’s side has a bunch of early cancers. Maybe I’m not just unlucky.

Just want to know what’s going on before it’s too late.

So let me get this straight - we’re now telling people to get their DNA scanned like it’s a Netflix subscription?

Next thing you know, they’ll be scanning babies at birth and sending them ‘cancer risk reports’ with their baby shower invites.

This isn’t medicine. It’s fear marketing dressed up as science.

And don’t even get me started on those ‘panel tests’ - they’re just fishing expeditions with a $500 price tag.

People are getting anxiety diagnoses because they got a VUS and panicked.

Meanwhile, the real problem? Poor diet, no exercise, and smoking. But nobody wants to talk about that.

Genetics is convenient. Blaming your DNA is easier than changing your life.

You know, in my village back home, we don’t have fancy gene tests. We have stories. Grandmothers whisper about who got sick young, who lost a sister at 35, who never had children because the womb wouldn’t hold life.

These aren’t data points - they’re echoes.

Now science is catching up to what our elders knew in silence.

I think this testing is less about fear and more about honoring those who came before us.

When you get a positive result, you’re not just learning about yourself - you’re carrying their story forward.

And if you’re lucky enough to get a clean bill? That’s not luck. That’s grace.

Maybe the real power isn’t in the gene - it’s in the courage to ask.

Not everyone gets to know why their family broke the way it did.

So if you can know - know it. Not for panic. For peace.

Big shoutout to the folks who wrote this - seriously, this is one of the clearest explainers I’ve ever read.

Just got my panel results back last month - VUS on CHEK2. Felt like my DNA just ghosted me.

Called my counselor, she said to check back in 18 months. Did, and guess what? Reclassified as benign. No joke, I cried.

Also - YES to the point about DTC tests. My cousin took 23andMe, saw ‘BRCA negative,’ and told her mom she’s ‘safe.’

Her mom got ovarian cancer 6 months later.

Don’t trust those ads. They’re not your friend.

And if you’re thinking about testing your kid? Wait. Let them decide when they’re old enough to handle it.

My sister’s 19 now, and she’s already booked her appointment. Proud of her.

Also - asymptomatic men with Lynch? Please get colonoscopies. I’m looking at you, Uncle Mike.

Love how this post breaks it down without hype 😊

My dad had colon cancer at 42 - no one in the family knew why.

Got tested last year - Lynch positive.

Now my whole side is getting screened. My brother’s colonoscopy showed a polyp - removed it. No cancer.

That’s the win right there.

Also, aspirin daily? My doc said it’s like a daily shield for Lynch folks.

Wish more people knew this stuff.

Thanks for sharing the real facts 💪

So let me get this straight - we spent decades telling women to do monthly self-checks, now we’re saying ‘just get your DNA scanned’?

Who’s really benefiting here? The labs? The insurers? Or the people?

Also, ‘reclassify VUS’? So I paid $500 for a mystery, and now you’re telling me to come back later for a free update?

That’s not progress - that’s a bait-and-switch with a PhD.

And don’t even get me started on GINA. Life insurance companies are already laughing in their boardrooms while we’re over here crying over our saliva tubes.

Genetics isn’t magic. It’s a tool. But right now, it’s being sold like a miracle cure for modern anxiety.

Also - yes, I’m still getting mammograms. No matter what my genes say.

My brother got BRCA2 positive. Had a mastectomy. No cancer. Just prevention.

Worst part? He waited 3 years because he was scared.

Don’t be him.

Test. Act. Move on.

Life’s too short for fear.

Of course they say ‘don’t worry about insurance’ - they’re not the ones getting denied coverage after a positive result.

And who’s paying for all these panel tests? The middle class?

Meanwhile, rich people get full-body scans and personalized oncology.

Meanwhile, I’m supposed to be grateful because I got a ‘free’ test through my ‘affordable’ insurance?

Yeah right.

This isn’t medicine. It’s a class divide with a DNA twist.

Did you know that in 2024, over 400,000 people had their genetic data leaked?

And you’re telling me to hand over my DNA to some lab so they can ‘help’ me?

What if the government gets it? What if China buys the database? What if they use it to target people with BRCA mutations?

They already track your social media - now they’ll track your genes?

And you call this ‘progress’?

This isn’t science - it’s a biometric surveillance pipeline.

And if you’re not scared, you’re not paying attention.

My cousin got tested. Now she’s getting flagged by her life insurer.

That’s not empowerment. That’s exploitation.

And don’t tell me about GINA - it’s full of holes.

They’re building the future, and we’re handing them the keys.