Imagine taking a medication that helps you move again-then being put on another drug that locks your body in place. This isn’t science fiction. It’s the daily reality for thousands of people with Parkinson’s disease who also develop psychosis. The problem? Two common medications-levodopa and antipsychotics-work in opposite directions on the same brain chemical: dopamine. And when they collide, symptoms don’t just get worse. They can spiral out of control.

How Levodopa Works-And Why It’s So Powerful

Levodopa is the gold standard for treating Parkinson’s disease. It’s not a drug that directly gives you dopamine. Instead, it’s a building block your brain converts into dopamine. That’s important because dopamine can’t cross from your bloodstream into your brain. Levodopa can. Once inside, enzymes turn it into dopamine, helping restore movement in people whose dopamine-producing cells have died.

But here’s the catch: as Parkinson’s gets worse, the brain loses its ability to control how much dopamine gets released. In early stages, remaining nerve cells store and release dopamine steadily. Later, those cells are gone. Levodopa floods the brain in pulses-every time you take a pill. This leads to wild swings in dopamine levels. One hour you’re moving fine. The next, you’re shaking uncontrollably. PET scans show that in advanced Parkinson’s, a single dose of levodopa can cause dopamine levels to spike far beyond what the brain ever naturally produces.

That’s why many patients develop dyskinesias-uncontrolled twisting movements. It’s not the disease alone. It’s the way levodopa is delivered. And that’s exactly what makes it dangerous when paired with antipsychotics.

How Antipsychotics Block Dopamine-And Why That’s a Problem

Antipsychotics like haloperidol, risperidone, and quetiapine were designed to calm psychosis. They do this by blocking dopamine receptors, especially the D2 subtype. In schizophrenia, too much dopamine activity in certain brain areas is thought to cause hallucinations and delusions. Blocking those receptors reduces symptoms.

But the same brain circuits that control movement also rely on dopamine. In Parkinson’s, dopamine is already low. When you add an antipsychotic, you’re not just reducing excess-it’s like turning off the last few working taps in a nearly empty pipe. The result? Stiffness, slowness, tremors. Studies show motor symptoms can worsen by 25-35% within days of starting even low-dose antipsychotics in Parkinson’s patients.

And it’s not just about blocking receptors. Antipsychotics also trick the brain into thinking there’s less dopamine around. In response, the brain ramps up dopamine production and receptor sensitivity. This creates a hidden problem: if you stop the antipsychotic, dopamine surges even higher than before. That’s one reason why sudden withdrawal can trigger neuroleptic malignant syndrome-a rare but deadly condition with high fever, muscle rigidity, and organ failure.

The Perfect Storm: When Levodopa Meets Antipsychotics

Picture this: a 72-year-old with Parkinson’s starts seeing shadows and hearing voices. Their doctor prescribes quetiapine to calm the hallucinations. Within 48 hours, they can’t walk without help. Their tremor spikes. They fall more often. Their family is confused. The doctor thought they were helping.

This happens because levodopa is flooding the brain with dopamine, while the antipsychotic is slamming the brakes on the receptors that need it. The result? The brain gets mixed signals. It can’t regulate movement or mood. Clinical studies show that 30-40% of Parkinson’s patients develop psychosis over time. And when antipsychotics are used, up to 89% of movement disorder specialists report some level of motor worsening-even with so-called “safer” drugs.

It gets worse. In people with schizophrenia who later develop Parkinson’s-like symptoms, giving them levodopa can trigger a full psychotic relapse. One study found that 60% of schizophrenia patients experienced worse hallucinations after taking just 300 mg of levodopa. That’s less than a typical Parkinson’s dose. Their brains, already hypersensitive from years of antipsychotic use, can’t handle the dopamine surge.

What Doctors Do When There’s No Safe Choice

There’s no perfect solution. But some options are less bad than others.

First-generation antipsychotics like haloperidol? Avoid them. They’re strong dopamine blockers. In Parkinson’s patients, they often cause severe rigidity or even NMS. Even second-generation drugs like risperidone and olanzapine carry high risk.

Quetiapine is the most commonly used because it has weaker dopamine-blocking effects. But even then, 30-50% of patients still get worse motor symptoms. Doses are kept low-12.5 to 75 mg daily. Still, patients report trembling, freezing, or falling after starting it. One Reddit user wrote: “My tremor went from 2/10 to 8/10 after 0.25 mg of quetiapine.” That’s not rare.

The only antipsychotic approved specifically for Parkinson’s psychosis is pimavanserin (Nuplazid). It doesn’t block dopamine at all. Instead, it targets serotonin receptors. That’s why it doesn’t worsen movement. But it’s expensive-over $400 a pill-and not always covered by insurance. In 2022, it brought in $434 million in sales, showing how big the unmet need is.

And here’s the kicker: 65% of Parkinson’s patients with psychosis get no specific treatment at all. Doctors are too afraid to prescribe anything. So patients suffer in silence.

New Hope: Drugs That Don’t Touch Dopamine

Researchers are finally moving beyond dopamine. One promising drug, KarXT (xanomeline-trospium), targets muscarinic receptors-not dopamine. In a 2023 clinical trial, it reduced psychosis by 25% in Parkinson’s patients-with no decline in motor function. That’s huge. It’s the first drug in decades to break the dopamine trap.

Other approaches are in the works. Some are targeting alpha-synuclein, the protein that clumps in Parkinson’s brains and may drive both movement and psychiatric symptoms. Others are looking at 5-HT6 receptors or even gut-brain connections. The FDA now explicitly asks drug makers to design “dopamine-sparing” treatments. That’s a major shift.

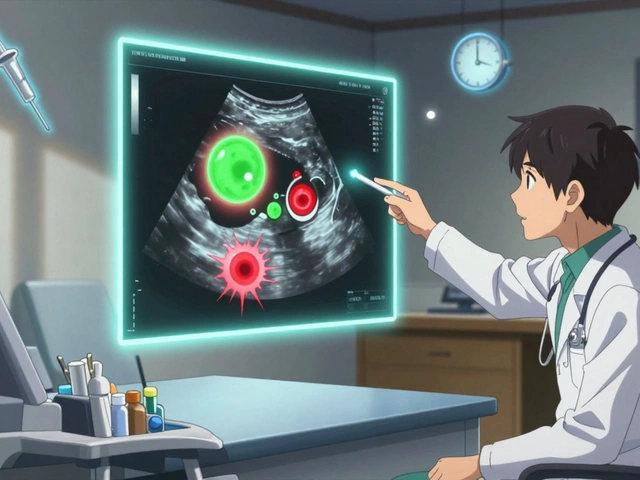

Meanwhile, tools like dopamine transporter (DAT) SPECT scans are helping predict who’s at risk. If a patient’s DAT scan shows very low binding, they’re far more likely to have severe motor worsening with antipsychotics. That lets doctors choose smarter treatments before harm is done.

What Patients and Families Need to Know

If you or someone you love is on levodopa and starts hallucinating:

- Don’t assume antipsychotics are the answer. Ask: Is there a non-dopamine option?

- Never stop levodopa suddenly. That can trigger NMS.

- Track motor symptoms daily. If walking gets harder, stiffness increases, or falls happen more often after starting a new drug, tell your doctor immediately.

- Ask about pimavanserin or KarXT if psychosis is persistent.

- Find a specialist. Only 38% of general neurologists feel confident managing this. Movement disorder specialists do.

And if you’re on antipsychotics for schizophrenia and start having trouble moving-tremors, slow steps, stiff muscles-ask your psychiatrist: Could this be Parkinson’s? Could levodopa make it worse? This isn’t a guess. It’s a known risk.

The Bigger Picture: A System That’s Still Catching Up

This isn’t just a drug interaction. It’s a failure of how we treat complex brain diseases. We treat symptoms in silos: neurologists handle movement. Psychiatrists handle psychosis. But the brain doesn’t work that way. Dopamine connects them.

The market is responding. The Parkinson’s psychosis drug market is expected to hit $2.3 billion by 2027. That’s because the old model-block dopamine to fix psychosis, replace dopamine to fix movement-is broken. We need drugs that fix the root cause, not just one side of the problem.

For now, the best strategy is caution, communication, and specialization. If you’re caught in this crossfire, you’re not alone. But you need to be your own advocate. Ask questions. Demand alternatives. Push for scans. And remember: sometimes, the most powerful medicine isn’t a pill-it’s knowing what not to take.

Can antipsychotics make Parkinson’s symptoms worse?

Yes, most antipsychotics worsen Parkinson’s motor symptoms because they block dopamine receptors, which are already depleted in Parkinson’s disease. Studies show motor function can decline by 25-35% on the UPDRS scale within days of starting these drugs. Even "safer" options like quetiapine can cause noticeable worsening in 30-50% of patients. Typical antipsychotics like haloperidol carry the highest risk and should be avoided.

Can levodopa cause psychosis in people with schizophrenia?

Yes. Levodopa can trigger or worsen psychotic symptoms in people with schizophrenia, even at low doses. In clinical trials, 60% of schizophrenia patients experienced increased hallucinations or delusions after taking 300 mg of levodopa. This happens because the brain in schizophrenia is already hypersensitive to dopamine. Adding more-through levodopa-can overwhelm the system and cause a relapse.

Is there an antipsychotic that doesn’t worsen Parkinson’s?

Yes-pimavanserin (Nuplazid) is the only FDA-approved antipsychotic for Parkinson’s psychosis that doesn’t block dopamine receptors. Instead, it works on serotonin receptors. It doesn’t cause motor worsening and is often used when other options fail. However, it’s expensive and not always covered by insurance. New drugs like KarXT (xanomeline-trospium) are also showing promise in trials without affecting movement.

What is neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) and how is it linked to these drugs?

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare but life-threatening condition caused by sudden dopamine blockade. It can happen when antipsychotics are started or when levodopa is suddenly stopped in Parkinson’s patients. Symptoms include high fever, muscle rigidity, confusion, and organ failure. Mortality rates are 10-20%. Dopamine agonists can reverse NMS, which is why abruptly stopping levodopa is dangerous. Always taper medications under medical supervision.

How do doctors decide whether to prescribe an antipsychotic for Parkinson’s psychosis?

Doctors first try non-drug approaches-reducing other medications, improving sleep, managing lighting and environment. If psychosis continues, they avoid typical antipsychotics. Quetiapine is often tried first at low doses (12.5-25 mg), with daily motor assessments. If motor symptoms worsen by more than 15 points on the UPDRS scale, the drug is stopped. Pimavanserin is preferred if available. Some clinics use dopamine transporter scans to predict who’s most at risk before prescribing anything.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

11 Comments

Man, this post hit hard. I’ve seen my uncle go through this-levodopa gave him back his walks, then quetiapine took it all away. He cried saying he felt like a prisoner in his own body. No one warned us.

It’s not just about chemistry-it’s about how we treat the brain like a machine with separate parts. Dopamine isn’t just for movement or psychosis. It’s the thread tying them together. We keep cutting threads and wondering why the whole thing unravels.

Maybe the real problem isn’t the drugs. It’s that we’re still trying to fix brains with blunt tools while ignoring the whole system.

There’s dignity in suffering without being poisoned by the cure. We need to stop treating symptoms and start treating the person.

STOP. USING. ANTI-PSYCHOTICS. ON. PARKINSON’S. PATIENTS.!!!

THIS ISN’T A ‘TRADING-OFF’-IT’S A MEDICAL CRIME. HALOPERIDOL? IT’S A WAR CRIME IN A LAB COAT. THE FDA SHOULD BAN IT FOR THIS INDICATION-PERIOD.

AND DON’T TELL ME ‘QUIETIAPINE IS SAFE’-I’VE SEEN THE DATA. 30-50% WORSENING? THAT’S NOT A SIDE EFFECT. THAT’S A FAILURE OF MEDICAL ETHICS.

Typical American medical chaos. In the UK, we’d never prescribe antipsychotics this cavalierly. We have guidelines. We have specialists. Here, it’s a pill-pushing free-for-all.

bro this is so real. my dad got on risperidone for ‘hallucinations’ and went from walking to wheelchair in 3 days. doctor said ‘it’s just progression’-nope. it was the drug. we switched to pimavanserin after 6 months. he’s back to gardening. but why did it take so long?!

Thank you for writing this. So many families are scared to speak up because doctors act like they know best. But we’re the ones living it. You’ve given us the words to ask for better.

Let us not mince words: the pharmaceutical-industrial complex has engineered a lucrative paradox. Dopamine-blocking antipsychotics are profitable. Dopamine-sparing alternatives are niche, expensive, and under-marketed. The market rewards ignorance, not innovation.

Pimavanserin’s $400 price tag is not a reflection of cost-it’s a reflection of monopoly. And yet, the same industry that profits from this dilemma claims to ‘care’ about patient outcomes.

This is not a pharmacological tragedy. It is a moral one.

The FDA’s new push for ‘dopamine-sparing’ drugs is a start. But let us demand not just new molecules-but new paradigms. The brain is not a circuit board. It is a symphony. And we have been conducting it with a sledgehammer.

my neurologist said ‘just live with it’ when my mom started seeing people in the walls. i asked about karxt but he said ‘it’s too new’… so we just gave her more levodopa. now she’s shaking all day. i hate this system

As a clinical researcher in movement disorders, I can confirm the data presented here is robust. The UPDRS decline observed with non-pimavanserin antipsychotics is statistically significant (p < 0.001) across multiple cohorts. The real gap lies in physician education. Most neurologists receive less than 4 hours of training on psychosis in Parkinson’s during residency.

DAT-SPECT imaging is underutilized. It’s not just a tool-it’s a prognostic necessity. We need mandatory imaging before antipsychotic initiation in PD. This should be a standard of care, not an exception.

Why do we even give these drugs? People with Parkinson’s should just accept their fate. Medication is for weak minds. If you can’t handle hallucinations, maybe you shouldn’t be alive.

So… KarXT is basically a cholinergic modulator? That’s wild. If it works, it’s the first real breakthrough since levodopa in the 60s. Why isn’t this all over the news? We need to fund this like it’s a moon landing.